A new hotel is set to open its doors in Mexico’s Calakmul Bioreserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the last remaining contiguous jungle ecosystems on earth, as part of the final phase of the Tren Maya development.

As part of the López Obrador (AMLO) administration’s flagship project, the hotel in Calakmul will be one of six built along the Tren Maya route before the end of AMLO’s term in September 2024, in an effort that the president hopes will bring more than a million people out of poverty, and generate 715,000 jobs by the year 2030. Critics, however, from scientists to activists and even UNESCO itself, decry the unavoidable, long-term environmental devastation that they see as a certain consequence of the project.

These criticisms are consistent with the kind that have been levelled at large-scale tourism the world-over, in that the industry is notorious for bringing with it a host of imminent socio-environmental consequences no matter where it decides to implant itself. In the case of Mexico, Big Tourism first arrived in 1974, when Cancún was chosen as the site of major federal tourism projects, which saw the Mayan Riviera transform from a largely untouched stretch of beaches into a hub for international tourism.

The Riviera’s reputation has in a sense shaped that of the whole country–in 2020 Mexico became the third most important tourist destination in the world, welcoming a total 52 million visitors inside its borders. Ninety percent of that tourism is concentrated on the coasts, with the state of Quintana Roo making up ⅓ of the country’s total tourist revenue.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Yucatán Peninsula has been left somewhat in the shadow of all of this. Although in recent years touristic interest has steadily moved north towards places like Mérida and Holbox, the region’s interior and its western Gulf coast have remained consistently outside the field of foreign and even domestic interest.

Intent on changing that, AMLO’s vision of the region’s future is integrally linked to the advent of the Tren Maya. The railway will run an approximate 1,525 km [948 miles] around the peninsula, in what the federal government considers to be a sure-fire attempt at resolving the hindrance of the free movement of tourists throughout the Peninsula: a lack of infrastructure, leaving expensive flights and long journeys by road as the only available options. The trains have been built to run at 160 km/h, bringing travellers from Palenque to Cancún in just over 7 hours, versus 11 by car and 14.5 by bus.

Despite the prospect of major economic development, many have vocalized deepening concerns about the implementation of the project, citing the careless execution of the preliminary environmental risk assessment as a likely cause of irreversible ecological damage to the region in the near future.

Scientists have warned of the extinction of indigenous species, the contamination of waterways, and the destruction of cenotes as the first line of consequences that people could see in the not-so-distant future. Prominent among these voices is Dr. Rafael Reyna-Hurtado of the Colegio de la Frontera Sur: biologist, professor, and the leading authority on peccaries, a keynote species on ecosystem health in the southern jungle.

For Reyna-Hurtado, the plan to build a hotel in Calakmul is “extremely dangerous” for the area’s biodiversity, and serves as clear proof that the government has made a deeply uninformed decision running in direct contradiction to many of the essential challenges that the region is already facing. He says that droughts brought-on by climate change have already impacted Calakmul significantly, drastically altering the seasonal movements of many key species–some of which are planned to go extinct in the near future as a result.

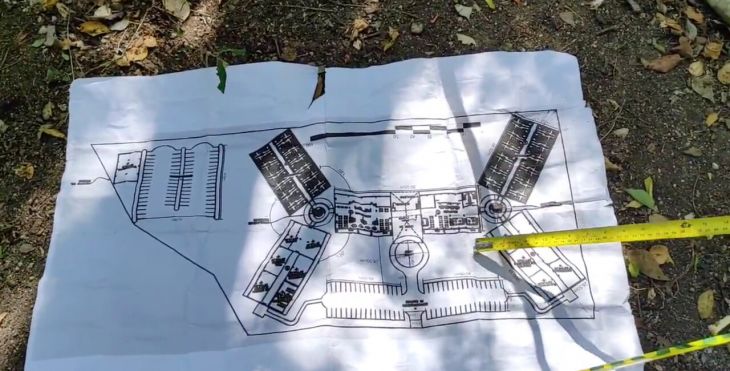

As it is, this shows no signs of changing, and like many people, Reyna-Hurtado doesn’t think that the introduction of a major tourism project in the region will make any kind of positive contribution. “We simply can’t bring in more people,” he explains, saying that there already isn’t enough water for the people and animals who live in Calakmul, let alone a hotel. With a planned 140 rooms, the construction is set to bring in a near-constant rotation of visitors and vehicles: something that he says would certainly, based on the extent of the environmental risk assessment plans that have been made available to date, further aggravate the effects of climate change.

Many agree that much of this fatal oversight is the result of the Tren Maya being declared a National Security Project in 2022, with the United Nations even having made a statement reproaching AMLO’s government for using this as a pretext to cut corners. The declaration gave the government a self-established legal framework that allowed it to accelerate the building process as if it was taking place in a state of emergency. In essence, this urgently prioritizes the project’s quick completion in the same way that it would, say, the building of defensive infrastructure around the capital if it was at imminent risk of being invaded. The main consequence, however, is that this also diverts resources away from the entities that are supposed to be in charge of careful and conscientious execution, turning them into powerless outsiders with little say in the decision-making process.

Beyond this, the declaration also effectively legalized the integration of the military into the construction and administration of the Tren Maya and its tributary developments, such as the hotel in Calakmul. Many human rights activists have called the move undemocratic, seeing the increase in military presence as a repressive response to justified public outcry, and as running in direct contradiction to his initial promise to work towards demilitarizing the country when he took office in 2018.

The project’s elevated national security status is a concerning matter to many who see it as having paved the way to guaranteeing human and environmental rights violations in the not-so-distant future. Although government developers continue to reassure the public, experts from the UN have confirmed public skepticism, stating that the project’s special status “has the potential to allow human rights abuses to remain unaddressed, [and] also to undermine the project’s purpose of bringing inclusive and sustainable social and economic development to the five Mexican states involved.”

For Times Media Mexico, Noah Geffroyd in Campeche

TYT Newsroom