As dynamic a landscape as any you’ll find on the shore, the ocean floor is home to some of the best adapted creatures on the planet. Vast plains, deep canyons, and the largest mountain chain on earth all sit – virtually untouched and unchanging for hundreds of thousands of years – deep beneath the surface of the water.

Untouched that is, until around 1868, when iron ore was pulled to the surface by a dredging ship to the north of the Russian coast. Over the following decade it was discovered that the rock of the ocean floor contains a wealth of minerals such as zinc, silver, platinum and gold, far in excess of the mineral deposits already being mined on land.

Scientists, environmentalists, policy makers, and the everyday citizen are all looking for solutions which will sustain the population over the coming decades. At present, this includes an increasing mineral requirement per capita for the creation of technology which we take for granted every day, such as laptops, and for the creation of solar power, electric cars, and of course the current 3.5. billion smartphones being used worldwide.

In 1982, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea established the Law of the Sea Treaty, a document which stated that “the seabed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources, are the common heritage of mankind.” This same UN Convention also took the first steps in the establishment of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the body responsible for the regulation of the exploration and exploitation of minerals in the international seabed.

But far from protecting the oceans from the harmful effects arising from mining activities, the ISA has largely ignored environmental concerns and shown itself to be on the side of the deep sea mining companies, entering into thirty 15-year contracts with countries across the globe which license the exploration of the deep seabed for minerals, 18 of which are located in the Clarion-Clipperton zone off the west coast of Mexico.

The Clarion-Clipperton zone is an area in international waters which is largely unexplored, and which is thought to contain high levels of the desirable minerals. It is also where scientists discovered the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, an active hydrothermal vent which spontaneously produces hydrocarbons – the building blocks of life on earth – and which is posited to be where the first organisms on earth evolved. The discovery of life in the deepest recesses of the ocean changed our views of the boundaries of life itself: if such a diverse ecosystem could evolve, devoid of light, under a huge amount of pressure, and sometimes in blistering heat, then there is reason to suppose that the life on other planets is not a farfetched dream, but a realistic probability. Indeed, in looking to what life on other planets may look like, NASA scientists look more regularly to the deep oceans than they do to outer space.

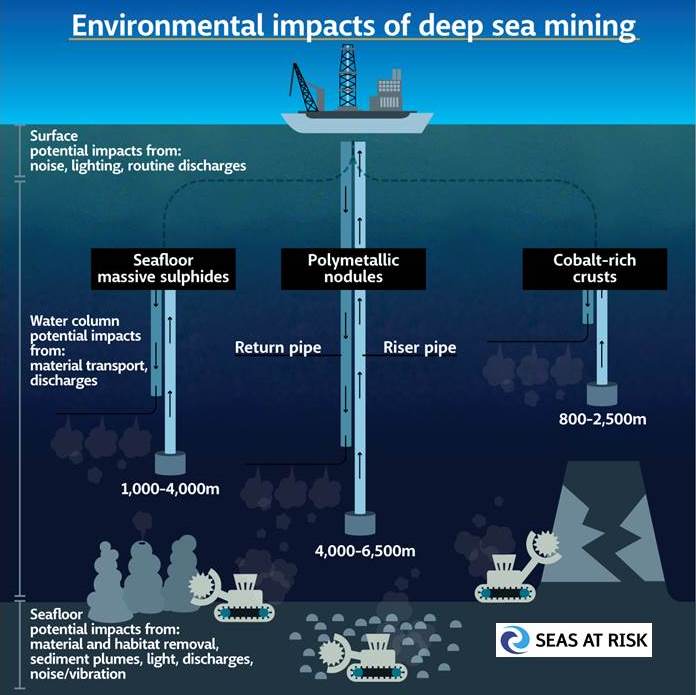

infographic deep sea mining by seas-at-risk.org

However, like many areas of the ocean, the Lost City is under threat from the deep sea mining industry, after the area was allocated to Poland by the ISA as a mining exploration concession site. It is notable that a recent Greenpeace report criticised the ISA for never once having turned down a license application, even where applicants were looking to explore ecologically sensitive areas like the Lost City.

The impact of human activity on ocean ecosystems already seems abundantly clear: overfishing, huge swirling gyres of rubbish, and billions of pounds of polymer being flushed into the ocean are all taking their toll on life beneath the surface. Scientists also estimate that around a third of the carbon dioxide generated on land is absorbed by underwater organisms, such as microbes, living on the very same ocean nodules which miners are planning to exploit. And yet, despite all of this, we still know pathetically little about life on the seafloor. The ecosystems in the deep sea are crucial to the health of the oceans and, indeed, to life on earth, often in ways which we do not yet fully understand.

At full capacity, mining companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Ships on the surface will draw thousands of pounds of sediment upwards using a vast hose, extract the desired mineral, then flush the slurry back into the ocean. Needless to say, such an operation would have a profound, untold environmental impact. As the detritus is returned to the sea, poisonous chemicals such as lead and mercury are likely to poison the surrounding waters for miles, the remainder drifting in the current until it settles on nearby ecosystems.

Opening up an industrial frontier in the largest, and most unexplored, ecosystem on the planet poses a significant environmental risk which will only exacerbate the biodiversity and climate crises facing the natural world. The nascent deep sea mining industry is suggesting that its development is essential, and inevitable, in a lower carbon future – but the ocean is not being mined yet. What we need is a moratorium on deep sea mining until we understand the complex workings on deep sea ecosystems, and until we can gauge the impact of mining on the fate of the global environment. It is essential that we put conservation, and not exploitation, at the heart of the way we choose to approach our oceans.

For The Yucatan Times / Times Media Mexico

Shannon Collins

—

Shannon Collins is a freelance writer, contributing to a variety of publications. As well as working with environmental organisations, she is pursuing a MA in English Linguistics at University College London.