The Mayan palace was discovered in the archaeological zone of Kulubá, Yucatán. The construction, located within this pre-Hispanic Mayan city, is approximately 55 meters long (180.5 ft) by 15 meters (49.2 ft) wide and 6 meters (19.6 ft) tall.

YUCATÁN, Mexico (Times Media Mexico) – 37 kilometers southeast of the city of Tizimin in Yucatan, Kulubá is located. It is quite an interesting Mayan archaeological site since everyday something new shows up.

The name Kulubá, according to the Maya language specialist William Brito Sansores (La escritura de los mayas, 1981), is allegedly formed by the words “K’ulu”, which refers to a kind of wild dog, and “ha”, water.

The archaeological zone of Kulubá, in Yucatán, is home to a 55-meter-long palace, according to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

“This work has confirmed the existence of a palace to the east of the main square of Group C, through the liberation and recognition of the base, the stairways and a crossing with pilasters, at the top, which would have been used by the elite of the place,” the INAH explained in a statement.

The construction, located inside this pre-Hispanic Mayan city, is approximately 55 meters long by 15 meters wide and 6 meters high.

Kulubá Yucatan, Palace Photo: INAH

The construction materials indicate that there were two phases of occupation: one in the Late Classic period (600-900 AD) and another in the Terminal Classic period (850-1050 AD).

“In the Terminal Classic is when Chichén Itzá became a prominent metropolis in the current Yucatán,–and– it extended its influence over sites like Kulubá,” explained archaeologist Alfredo Barrera.

Along with this palace, the experts explored four other structures in the plaza of the so-called architectural Group C: an altar, two vestiges of living spaces and a round construction that is believed to have been an oven.

Kulubá is an archaeological zone located 37 kilometers from the municipality of Tizmín that is still being studied and recovered.

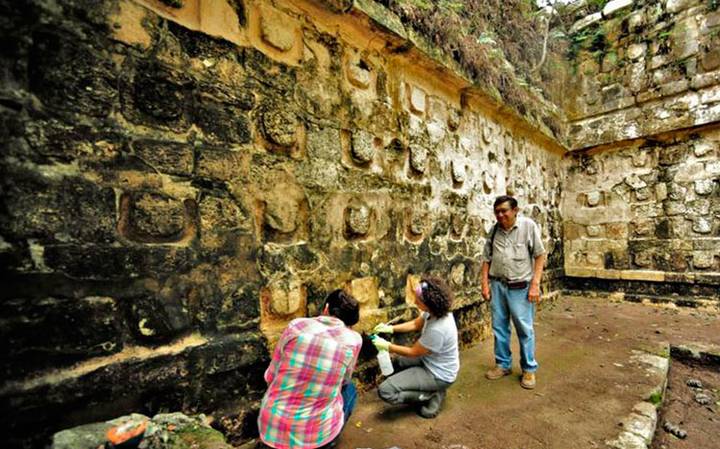

Archeologists at Kulubá Yucatan, Palace Photo: INAH

The people in charge of the work of the multidisciplinary project are specialists in archaeology and restoration.

“Throughout the 20th century, Tizimín ceded most of its forest land to agricultural and livestock use. This means that the experts who are now restoring the Mayan buildings to their former glory not only live alongside spider monkeys and other species of flora and fauna, but also give priority to the fact that the archaeological zone is distinguished by its natural and cultural balance” said INAH.

Kulubá Yucatan, entrance to the palace Photo: INAH

“All these exploratory and conservation actions are the beginning of the work that the INAH carries out to recover, research and disseminate among the public the cultural and natural heritage of Kulubá, a place that increases its heritage attraction and regional sustainability” concluded the INAH.