[Link to “Surprising History in Yucatán” — Introduction to the Series]

President Porfirio Díaz came to Yucatán with a short list of things he needed to do.

The announced purpose for the visit in 1906 was routine and boring — to attend the Governor’s inauguration and dedicate some new public works. In reality, Díaz arrived with the following to-do list in his vest pocket:

Item: Patch things up with the Yucatecans for taking away half their state.

Item: Squelch rumors of slave labor on the henequen plantations.

Of course, there was other business as well, mostly along the lines of exchanging flattery and support with local political allies. Yucatán’s governor, rich and powerful Olegario Molina Solís, had just been re-elected to a second term, an action as controversial as the President’s own multiple re-elections. And the wealthy state of Yucatán itself, isolated from the rest of Mexico and always with a streak of independence, was not as firmly under his control as he would have liked. A good, strong dose of Díaz power and cult of personality could help.

The main list needed his attention, though. Barely three years before his arrival, Díaz had divided Yucatán state to create the new Territory of Quintana Roo. With the new territory, Díaz had gained Federal and personal control over valuable land grants and export duties. But Yucatán, bitterly remembering its losses of Belize, Petén, and Campeche over the centuries, was still protesting over this latest outrage. Could he use patronage effectively to quiet down the opposition?

On the second item, perhaps even more important, Mexico was beginning to receive bad international publicity about mistreatment of henequen workers. This had the potential to discourage the foreign investment that was the basis for the Díaz economic strategy. The rumors, true or not, had be put down convincingly.

It turned out that the business about the henequen workers would require some astonishing sleight-of-hand, as elaborate as it was cynical and dishonest.

Díaz was coming to Yucatán at the height of his political power. In seven terms as President of Mexico, totaling nearly three decades, he had brought peace, stability, modernization, and economic growth to the nation. He transformed an empty treasury and huge foreign debts into budget surpluses, introduced free public education, and defused dangerous conflict between Government and Church.

And yet, today there are no towns named for him, not even any streets, no portraits on the stamps or currency, no monuments of significance. Despite the decades of his trademark “Order and Progress,” Díaz remains a deeply controversial figure, considered by historians to have been a dictator.

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori emerged from poverty in the indigenous depths of Oaxaca. He was clearly mestizo, his mother of Mixtec ancestry. (Stories of a Japanese grandfather are almost certainly false.) He was a genuine military hero in the Reform War and during the French Intervention. Benito Juárez relied on him and trusted him completely. But in 1876 he overthrew the successor of Juárez on the grounds, ironically, that he had been re-elected too many times.

A political genius, Díaz dethroned the regional bosses, who had long kept Mexico from becoming a real nation, and appropriated their power. Separatist tendencies lost force, and the leaders of Mexico answered directly to him. He suppressed the media and controlled the courts. He imprisoned opponents and ordered police to shoot protesters. Political parties essentially disappeared, replaced by patronage networks based on alliances of family and friends, linked directly to Díaz. Overt fighting was replaced by personal intrigues, often carried on through newspapers and pamphlets, with constant maneuvering for approval by Díaz. The “obligatory cooperation” Díaz enforced was not his invention but had roots in the Aztec Empire and Viceregal New Spain.

Díaz relentlessly pushed for economic progress, development, and profits with little regard to social costs. Mexico was open for business, and the influx of capital thoroughly transformed the nation to meet the needs of foreign countries, principally the United States. The rise of an urban working class coincided with oppression and exploitation of the rural poor.

When Díaz landed at Progreso on February 5, 1906, it was the first time any ruler of Mexico, whether President, Emperor, or Viceroy, had ever visited the Peninsula. He was 75 years old and, although his vanity and pride were undiminished, physical and mental decline were increasingly obvious to close associates. He was easily exhausted, his deafness was increasing, and he suffered terribly from gum disease.

The visit to Yucatán became a virtual deification of Díaz. It began with the state’s elite welcoming him at the pier. Accompanied by his second wife, Carmen Romero Rubio, Vice president Ramón Corral, a retinue of seventy government officials and dignitaries, and the domestic and foreign press corps, the President passed under two ceremonial arches and boarded a train for Mérida.

Organizers had laid down a branch railroad track to bring the President’s train to the glorieta at the northern terminus of the elegant new Paseo de Montejo. A recently erected statue of Justo Sierra O’Reilly stood at that point on the city’s edge, where the pavement ended and a road led out to the picturesque village of Itzimná. After an even larger welcoming ceremony, the party began its triumphant procession into Mérida.

Preparations in the capital had been underway for months. There had been nothing remotely like it since the visit by Empress Carlota forty years earlier. Streets were lavishly decorated, and the façades of buildings had been repaired and painted. Boatloads of flowers had been brought in from Veracruz. Upper-class residents spent fortunes on clothes and carriages. Visitors from other parts of Mexico and from abroad filled the hotels.

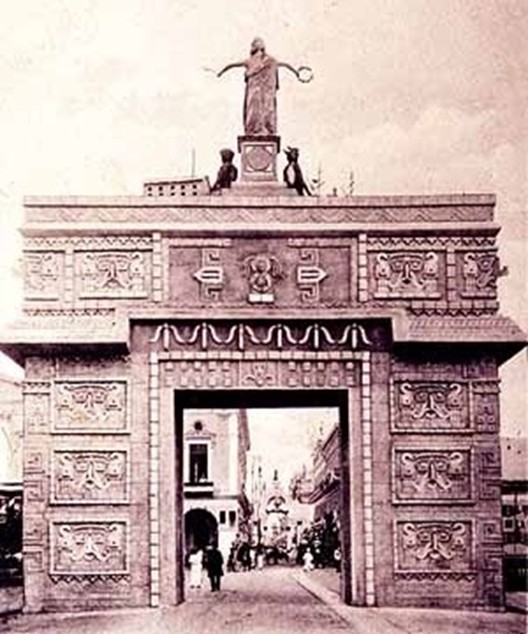

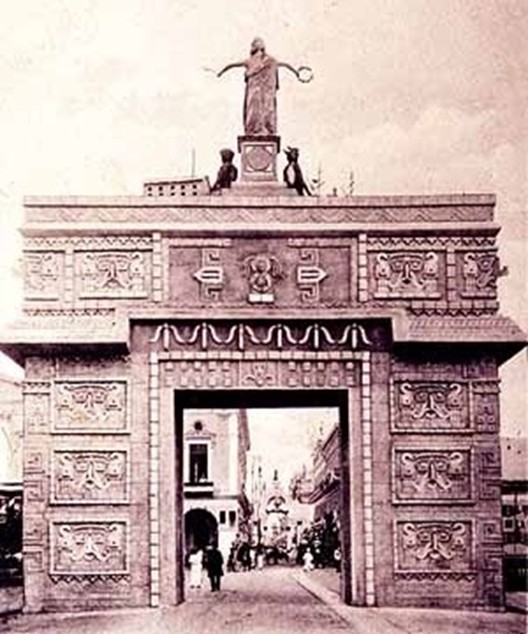

Most noteworthy were the twelve beautifully designed triumphal arches erected over streets. The city put up two, the business community one, and the Moctezuma brewery one. Seven were gifts from international communities and embassies: Cuba, Italy, Germany, Spain, the United States, Turkey, and China — the last created by a committee from San Francisco, California. The state government sponsored a centerpiece arch adjacent to the main plaza, designed in a ground-breaking neo-Maya style that later became popular. It included images of the important Maya rain god Chaak with a moustache added, the resemblance to don Porfirio and the intended message unmistakable.

The neo-Maya-style arch erected by the Yucatán State Government on present Calle 60 in front of Mérida’s cathedral. The repeated masks of the god Chaak are made to resemble the President.

(Photograph from a contemporary postcard.)

The President was taken through the arches on tours of the city — to museums, banks, the city hall, schools, the Literary Institute. The Governor showed off his newly paved streets. With all schools and businesses closed, thousands of people lined the routes. There was a torchlight procession, a parade, traditional dancing by happy workers, and a formal ball honoring the President’s wife. Vast sums were spent on single meals, gargantuan feasts with hundreds of attendees. A pageant with decorated floats illustrated the history of Yucatán, beginning in pre-Conquest times and culminating with an image of Díaz, the “Hero of Peace,” accompanied by a young woman costumed as winged victory. The only actual Maya people present in the historic spectacle were the laborers pulling the decorated wagons.

Díaz attended the Governor’s inauguration on February 6 — the nominal reason for the visit — and dedications of the “Benito Juárez” penitentiary, the “Leandro León Ayala” insane asylum, the “Agustín O’Horán” hospital, and the “Nicolás Bravo” elementary school. A bronze bust of the President was dedicated, and a major street — today’s Calle 59 — was renamed Avenida Porfirio Díaz.

Meanwhile, don Porfirio found time to deal with his Quintana Roo problem. He had already awarded Governor Olegario Molina land concessions of more than 800,000 acres — five times the area of the entire island of Cozumel. In exchange, Molina published newspaper articles supporting the President’s action and made efforts to put down public protests. Díaz bought off other influential opponents with large tracts of valuable tropical forest. Before he was finished, a third of Quintana Roo was in the hands of entrepreneurs from Yucatán, other Mexican states, and Belize, many fronting for North American interests. Money from land fees and export duties flowed into the Federal treasury, and Díaz hugely increased his personal fortune.

As for the slave-labor issue, the henequen millionaires worked hard to ensure that the President would find nothing to support the rumors. In fact, they had built their fortunes on a brutal labor system in which debt peonage and vagrancy laws created conditions much like slavery for many hacienda workers. But now they had to pass inspection by the mighty Díaz, or at least provide him with credible deniability. Díaz basically cared little about the oppressed Maya or other members of the lower classes. He had been using the Peninsula as a sort of national slave-labor gulag for political prisoners. He did care deeply about protecting the honorable image of Mexico, though.

On February 7, President Díaz traveled to the henequen hacienda Chunchucmil, 90 miles southeast of Mérida, the property of Rafael Peón Losa. It was an arduous three-hour journey by railroad, tramway, and carriage, and one has to wonder why the organizers did not select one of the many haciendas closer to the city.

The answer lies in story published in Mexico City by El Universal five years earlier. A contract worker named Felipe Juárez made headlines with a story that he had not been paid what he was due and had been detained and flogged before he was finally able to escape from Chunchucmil. Further, he had been advised that if he tried to file suit in Yucatán he would be drafted into the army. The story created a national scandal. Yucatecan politicians and landowners closed ranks around Rafael Peón, defending him as the most generous and admirable of employers and expressing their outrage at being called slavers. Peón wrote a letter to President Díaz denying everything and labeling Felipe Juárez as a troublemaker who was inciting workers to revolt. Although the story died down, Chunchucmil had been tabbed as an exemplar of plantation slavery and so was the obvious place to put the matter to rest.

The presidential party traveled the last two miles to Chunchucmil along a road strewn with flowers and lined with well rehearsed, cheering, flag-waving workers. They entered the estate through floral arches, with rockets firing in celebration.

The hosts escorted the President on a tour to inspect the henequen defibrillation machinery, boilers, drying racks, and packing plant; the hospital, pharmacy, store, and school (up to third grade); the chapel, gardens and orchard.

To put a definitive end to the “slavery” rumors, the delegation visited eight houses for workers. The palm-thatched huts were immaculate and freshly whitewashed. They had curtains on the windows, imported bentwood furniture, and sewing machines. The Maya residents were all wearing new clothes, some even tricked out with European-style hats. All expressed their comfort, satisfaction, loyalty, and gratitude.

In his speech later, after the mid-day luncheon for two hundred, Díaz said, “Some writers who do not know this country … have declared Yucatán to be disgraced with slavery. Their statements are the grossest calumny, as is proven by the very faces of the laborers, by their tranquil happiness.”

Of course, it was all fake. If not actually built for the occasion, the houses had seen a metamorphosis beyond recognition. The carefully selected actors certainly understood that any slip-up or honestly expressed complaint would cost their lives. As soon as the performance was over, everything — furnishings, clothing, curtains, sewing machines — went back to the stores in Mérida. The workers returned to their familiar life almost free of clothing or furniture.

Díaz departed to the prolonged cheers of the henequen millionaires celebrating their successful deception. The President may have seen through the carefully staged scam created for him, but he bought into it.

The presidential visit to Yucatán climaxed the next day with a banquet at Governor Molina’s Hacienda Sodzil, accompanied by a total eclipse of the moon. (The role of the planning committee in the latter is unclear.) On February 9, adulatory farewell ceremonies sent the visitors back to Progreso, where they cast off for Veracruz. The triumphal arches were soon taken down, the flags and flowers became litter. Governor Molina left for a vacation in Europe and on his return was promoted to a Cabinet position in the Díaz government.

The slavery rumors failed to die and soon culminated in full-blown publications — Barbarous Mexico by socialist muckraker John Kenneth Turner in the United States and The American Egypt by travel writers Channing Arnold and Frederick Tabor Frost in Britain. The international reputation of Mexico’s porfiriato was slipping badly, and the books fanned the growing flames of discontent in Mexico.

In a 1908 interview with a North American journalist, Díaz promised not to run for President again. But increasing political unrest led him to change his mind and do his “patriotic duty” in the election of 1910. He imprisoned his electoral rival and, after massive and obvious electoral fraud, declared himself the winner of an eighth term in office. The Revolution drove him from power, and he fled the country on May 31, 1911.

Today some historians are re-evaluating the Díaz regime. Foreign investment is in favor again, as neo-liberal economic policies have replaced the post-Revolutionary emphasis on nationalization and internal development. But it seems impossible to believe that Yucatecans will ever again regard Porfirio Díaz as the hero they did in 1906.

by Robert D. Temple

______________________________________

During his time in Mérida, Porfirio Díaz stayed in the mansion of don Sixto García, one of the most elegant residences in the city. It stood at the intersection of Calles 63 and 64, diagonally across from the Monjas church. In the 1980s the city allowed the mansion to be torn down to build a parking lot.

A marble plaque honoring Díaz was unveiled on the last day of the President’s visit in Mérida. The plaque was removed and destroyed after the Revolution, but holes from the bolts that anchored it can still be seen on the southeast corner of the Government Palace, the green building on the main plaza diagonally across from the cathedral.

Today’s explorers can visit the site of the Potemkin village created for the Díaz visit, Hacienda Chunchucmil. The abandoned but well preserved hacienda is in the center of the town of the same name, located off the Mérida-Campeche highway about 12 miles west of Maxcanú. The village soccer field now occupies the courtyard where Rafael Peón once had a pond with flamingos. The town lies within a large unrestored Maya archeological site, and the hacienda incorporates stones from ancient structures.

4 comments

My Dear Robert, You have done it again, another fascinating, detailed historical article about our beautiful part of the world. This is information that is so important for us to know.

GRACIAS !!!!!!!

Tonia Kimsey

Thank you for your king comments, Tonia, and best regards.

Bob, you know more about Yucatan than many YucateRcos.. Saludos compadre.

Not more than you, sir, but thank you for the endorsement. Your comments are always valued. Next month will be Alvarado, one of the good guys. Best to you.