The ancient Maya believed that valued consumables in the natural world — such as water, corn and honey — were “divine”, and under control of their gods.

Honey was probably their only source of sweetness, therefore, it was especially treasured in a culture that didn’t have sugar cane or sugar beets. And honey’s sugar content enabled it to be converted into a much more valuable commodity: liquor.

Native meliponines (abeja melipona) have been kept by the lowland Maya for thousands of years. The traditional Mayan name for this bee is “xunan kab”, meaning “(royal, noble) lady bee”. The bees were once the subject of religious ceremonies and were a symbol of the bee-god “Ah-Muzen-Cab”.

The bees were, and still are, treated as pets among the Maya. Families would have one or many log-hives hanging in and around their houses. Although they are stingless, the bees do bite and can leave welts similar to a mosquito bite.

The traditional way to gather bees, still favored among the locals, is find a wild hive, then the branch is cut around the hive to create a portable log, enclosing the colony.

The fermentation of honey was practiced by ancient cultures all over the world. And the Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula were no exception. So, they used to prepare this kind of beer using a recipe of honey, with corn and chilies.

“Booze” in ancient Mexican cultures

Henry Bruman, in his 1930 book “Alcohol in Ancient Mexico,” talked about the widespread consumption of Mexican beverages created from fermented honey.

Bruman’s book reconstructs the variety and extent of distillation traditions in the ancient cultures of Mexico, describing in detail the various plants and processes used to make such beverages, their prevalence, and their significance for local culture.

The art of distillation arrived in Mexico with the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. However, well before that time, native skills and available resources had contributed to a well-developed tradition of intoxicating beverages, many of which are still produced and consumed.

In the 1930’s Henry Bruman visited various Mexican and Central American Indian tribes to reconstruct the variety and extent of these ancient traditions. He discerned five distinct areas defined by the culturally most significant beverages, all superimposed over the great mescal wine region. Within these five areas he noted wine made from cactus, cactus fruit, cornstalks, and mesquite pods; beer from sprouted maize; and fermented sap from pulque agaves.

Outside the mezcal region he observed widespread consumption in the Yucatan of a wine made from fermented honey and balché tree bark, plus lesser-known beverages in other regions. He also observed the frequent inclusion in the fermentation process of alkaloid-bearing ingredients such as peyote and tobacco, plants whose roots or bark contain saponins—which act as cardiac poisons—and even poisons from certain toads.

Alcohol in Ancient Mexico also considers the relative absence of alcoholic drink in the southwestern United States, the introduction of sills following the Spanish conquest, and possible sources for the introduction of coconut wine.

Previously unpublished, the research presented by Bruman retains its relevance today, and it offers a fascinating glimpse at a traditional world that has now almost vanished.

Balché

Another Maya alcoholic beverage is the Balché, a kind of mead, an intoxicating beverage consumed by the ancient Maya and by some of their descendants today. These people make the drink in a trough or a canoe, which they fill with water and honey, adding chunks of bark and roots from the balché tree. The mixture begins to ferment immediately.

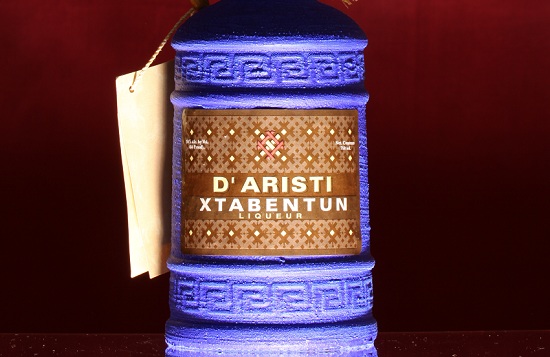

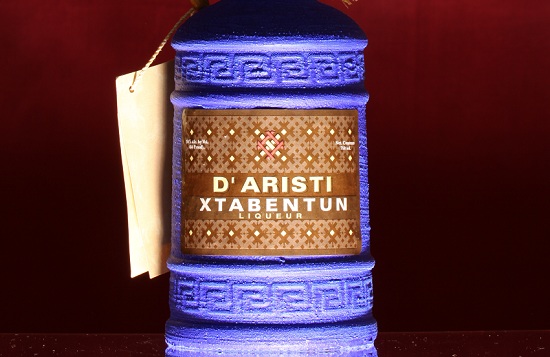

Xtabentún may have its origin in balché, a ceremonial liquor produced by the Maya (Photo: mayantravel.net)

During the fermentation process of such beverages, alkaloid-bearing ingredients — including hallucinogenic Mezcaline (peyote) or Psilocybin (mushrooms) — were sometimes added, making for a potentially psychotropic sip.

In gift shops throughout Yucatan are displays of xtabentun (ish-tah-been-tune), advertised as “liquor of the Maya.” Made only in this region, xtabentun is honey beer to which anise and distilled spirits are usually added.

The name “xtabentun” is derived from the legend of a woman named Xtabay, that literally means ‘Female Ensnarer’ in Mayan and refers to a Mesoamerican demon who seduces and kills young or old men who wander out of their homes after sunset.

Xtabentun may be taken straight or on the rocks. Some like to mix the liquor with coffee to make Mayan coffee or with tequila and lime to make a Mayan margarita.

Xtabentun is predictably sweet, with a strong anise flavor similar to Sambuca or Galliano (without the latter’s herbal complexity). This liquor’s aggressive sweetness can be mellowed by mixing with vodka, gin, rum or other clear spirits (depending on how “high” you want to get).

Dragon Fruit Martini

At Banyan Tree Mayakoba Hotel, La Copa bar, serves Xtabentún as a light, elegant martini. And here is the recipe if you want to DIY:

Ingredients:

- 3 ounces dragon fruit nectar

1 ounce xtabentún

¼ ounce lime juice

¼ hibiscus infusion or tea

Dragon fruit slice, for garnish

Combine all ingredients in a cocktail shaker filled with ice and shake. Strain into a coupe or martini glass and garnish with a dragon fruit slice.

Sources: