[“Surprising History in Yucatán” — Introduction to the Series]

The Caste War of Yucatán officially ended, after fifty-four years of horror, when a Mexican army occupied the Maya capital on May 4, 1901.

But the deep-rooted and lingering war really had no definitive final battle, no conclusive peace treaty. No Waterloo, no Appomattox. The end came several times. Or maybe not.

The interethnic conflict began in 1847, raged ferociously for a decade or so, then settled into guerrilla clashes and murderous raids. The cost was about a quarter of a million lives and hundreds of towns destroyed. The Yucatán Peninsula lost a third to half of its population, killed or forced to flee from the violence. The rebelling Maya, defending their culture against subjugation and the advances of capitalist agriculture, established and maintained an independent nation, roughly today’s state of Quintana Roo, with their capital at Chan Santa Cruz.

The independent Maya, known as the Cruzo’ob because of their adherence to the indigenous Speaking Cross religion, were sustained by trade with British Honduras (now Belize). They bought arms and other goods, paying with captured loot and with “taxes” charged to British woodcutters allowed to work in areas they controlled. Great Britain recognized the Maya free state as a de facto independent nation.

The war might have ended in 1884. Mexico re-established diplomatic relations with Great Britain, broken seventeen years earlier in retaliation for Britain’s recognition of the French-imposed Maximilian regime. Britain responded by acting as a peacemaker, sponsoring negotiations between the Spanish Yucateco state and the Maya Cruzo’ob state — while continuing the lucrative arms trade. A delegation of Maya leaders met with a Yucatecan representative, General Teodosio Canto, in Belize. They reached a peace agreement that afforded the Maya a measure of autonomy, selection of their own leaders, and an exchange of prisoners. The day after the signing, a drunken General Canto insulted one of the Maya leaders, Antonio Dzul. The Maya denounced the treaty and left in anger.

In 1887 the Maya formally requested that Britain annex their territory and place them under the protection of Queen Victoria. The British declined the offer. But this incident inspired talks between the Mexican and British governments aimed at pacifying things along their mutual border.

Mexican President Porfirio Díaz, working to put down several long-running Indian revolts, recognized that cutting off the arms supply was key to winning in Yucatán. A first step was to settle the long-disputed boundary between Mexico and British Honduras. The Spencer-Mariscal Treaty, signed in 1893, did that by establishing the Río Hondo as the boundary. Howls of protest arose from Yucatán over the loss of territory they believed to be theirs. Mexico resolved some outstanding debt problems, and the British agreed in principle to suppress the arms trade. In fact, little changed on the last point.

Within the Cruzo’ob nation, disputes over peacemaking and allocation of timbering proceeds were causing rapid changes in leadership. Central authority deteriorated, people were emigrating, and the number of effective troops was falling. A rare visitor in 1888 reported Chan Santa Cruz depopulated, although still used as a ceremonial and meeting place, with the Speaking Cross shrine heavily guarded. The Cross itself had been taken to Tulum and then, amid further political squabbles, moved to Chunpom, about midway between the two rival sanctuaries. In 1892, a British merchant opened a store in ruined Bacalar, undermining the isolationist leaders.

In 1896, actions got underway that led to the official end-of-the-war date five years later. Independent-minded Yucatán finally accepted that all-out Federal assistance was the only way to end the war. Mexican and Yucatecan troops established a headquarters for invasion at the abandoned town of Sabán, on the frontier east of Peto, about fifty miles northwest of Chan Santa Cruz. President Díaz selected General Francisco Cantón to be governor of Yucatán, a military man to support a joint military effort.

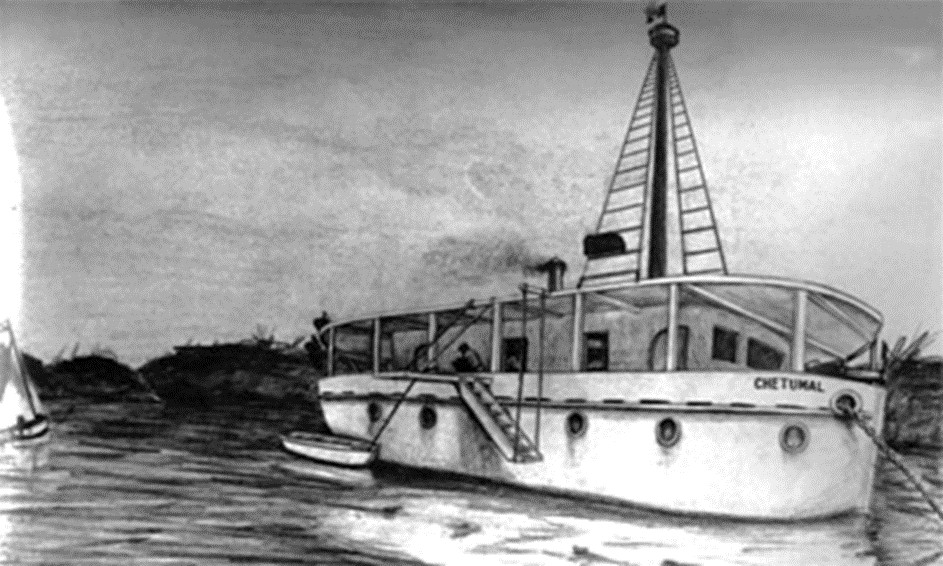

In a move to stop the flow of arms and timber proceeds to the Maya, Federal authorities ordered a young naval officer, Sublieutenant Othón Pompeyo Blanco, to establish a military station and customs post at the mouth of the Río Hondo. Blanco decided he preferred a floating fortress over a land-based one. His superiors accepted the plan, and Blanco supervised construction of a suitable vessel at New Orleans. It was a game-changer.

Blanco’s vessel, christened Pontón Chetumal, was an unpowered, tub-like barge. Built of cypress planks with an armor-protected deck, it was 62 feet long and 24 feet wide with a draft less than three feet. A single mast supported an armored crow’s nest. Armament consisted of one rapid-firing Hotchkiss cannon, one machine gun (a French mitrailleuse or possibly a U.S. Gatling), fifteen Winchester repeating rifles, six pistols, and eighteen machetes. Chetumal had a motor launch and small sailboat as auxiliaries.

His unusual vessel was towed to Belize City. There Blanco dealt with the delicate diplomacy of enforcing an international boundary on a river woodcutters had long considered their private waterway. The British authorities gave their assent, and on the afternoon of January 22, 1898, an American-flagged steamer towed Blanco with his twelve-man crew into Chetumal Bay and to their station off the Mexican shore at the mouth of the Río Hondo. Blanco’s men soon received a letter from the rebel Maya warning them to “leave or have their skulls converted to drinking cups.”

Unintimidated, Blanco recognized the need for an actual settlement, not just his floating fortress, to hold this strategic location. He recruited Mexican refugees and founded a town beside the bay on the left bank of the river. Under protection by his sailors, the settlers cleared the brush, put up barracks and a pier, and laid out sand streets. At dawn on May 5, 1898, and with great emotion, the first residents cheered the raising of the Mexican flag and sang the Himno Nacional Mexicano accompanied by a brass band. They called the town Payo Obispo in honor of a bishop — later archbishop and viceroy of New Spain — Payo Enríquez de Rivera y Manrique, who had stopped there briefly in the 17th century.

The humble barge Chetumal effectively intercepted the supply of arms, gunpowder, and timber revenue and provided a base for conducting reconnaissance on Maya strength in the region.

Then the serious troop build-up began at Sabán — seven battalions of Mexican regulars and three of state militia, equipped with modern five-shot Mauser rifles, machine guns, and rapid-fire de Bange field artillery. General Ignacio A. Bravo, a long-time military supporter of President Díaz, arrived to take command. A small, seventy-year-old man with a huge, drooping white moustache, Bravo was chosen because of his genocidal success against the Yaquis in Sonora. The General declared he was on a “humanitarian and civilizing” mission.

The British government urged last-minute negotiations, but neither the Maya nor the Mexicans had much interest.

Bravo initiated a “scientific” campaign. Well supplied, he progressed eastward on a road built through wide clear-cuts, establishing strong points connected by telegraph lines and field telephones. It was basically a construction project, with the military protecting the work gangs and the state government pouring in money.

Maya soldiers first opposed Bravo’s advance on December 27, 1899. Although they outnumbered the Mexican-Yucatecan army, the Maya found their dry stone walls were no match for artillery fire. Their shotguns, ancient muzzle loaders, and machetes were ineffective against modern weapons, and they were short on ammunition for the single shot Martini-Enfield rifles they bought from the British. As shot for their muzzle-loaders, they resorted to using bits of telegraph wires they had taken down and cut up. Bravo’s fortifications, clearings, and good communication precluded the ambushes they had used effectively for so many years.

In four months, Bravo’s army advanced thirty miles toward Chan Santa Cruz, building good wagon road and forts along the way. When the rainy season began in May 1900, the supply routes became impassable, a severe measles epidemic struck the Maya forces, and military action paused. Things resumed in early 1901, with the Maya attacking in force but unable to stop the relentless advance.

A simultaneous naval operation from Chetumal Bay advanced against light resistance and occupied the ruined and abandoned town of Bacalar on March 31, 1901. Forces under General José María de la Vega began advancing toward Chan Santa Cruz from the south. Vega also sent forces to land at a sand spit on Ascensión Bay called Vigía Chico; at Tulum; and at Xcalak, a deserted peninsula seaward of Chetumal Bay. The Maya nation was surrounded.

By Robert D. Temple

Next: The Power of General May

To be continued next month in The Yucatan Times — February 1, 2016

____________________________

Payo Obispo is now Chetumal, the capital of the state of Quintana Roo, and Chan Santa Cruz is the town of Felipe Carrillo Puerto. Both are full of interest and merit extended visits.

The Caste War Museum in Tihosuco is an essential destination for anyone interested in the history of the conflict.

1 comment

Wonderful article…Just a suggestion, perhaps a book about the history of the Yucatan should be forthcoming.

I would love to have one.

Mil Gracias, Tonia Kimsey